In The Leftovers, desirability emerges through the strategies that individuals use to survive the end of the world. Lily Scherlis and I wrote about Damon Lindelof's HBO series, The Leftovers on how the apocalypse transforms attraction, desire, and strategies for getting by.

In Violent Faculties, the real horror is not the gutting of a human but the gutting of the humanities. I wrote about Charlene Elsby's academic horror novel, Violent Faculties and the relationship between bureaucracy, rationalization, and horror.

Looking to the moments we emphasize in a life teaches us about the kinds of biography that motivate our present understanding of that life. I wrote about the fantasies that motivate biographical investigations of Michel Foucault.

Marker’s lesson, in part, is that the news is what you make it, but you cannot make it just as you please. I wrote about the history of artists and activists blending fiction and news on the occasion of the translation of Chris Marker's magazine writing.

For each scientific breakthrough, there are horrors. And there is the awe and stupidity of human responsibility. I reviewed Benjamín Labatut's The MANIAC to understand his use of fiction as a tool that represents the history of twentieth-century science and computing.

If TV has adopted crisis as its preferred narrative, it is because our world seems to be in a perennial one. In this essay, I analyze the rise of contemporary miniseries that are structured by narrative crisis as one way that we process a world that is increasingly shaped by widespread crisis and catastrophe.

Here, however, you will find no comprehensive account of what small press poetry is, was, or will be—and certainly no complete picture of the writers, publishers, and networks that make it run. Instead, we have assembled a Flood of histories, impenetrable and personal Jargons, and Lost Roads that connect only in remote places. For my last issue as editor of Chicago Review, I wrote an introduction to our feature on contemporary small press poetry.

The Novelist unfolds over a single, present-day morning during which Castro’s unnamed protagonist...does all the things writers do when they’re not writing, when they’re failing to write, and when they’re finally writing: surfing the internet, making coffee, walking the dog, taking a shit, not necessarily in that order. A review that articulates the limits and achievements of Jordan Castro's metafictional experiment.

Fiction such as The Employees offers a vital imaginative tool, not only for empathetic identification, but also for modeling the more ineffable ways that work has so deeply inscribed all of our lives. An essay about Olga Ravn's sci-fi absurdity as workplace novel.

To have a ghost, you must first have a past. This essay explores the literary history of haunted houses, using Nathaniel Hawthorne's The House of the Seven Gables as a jumping off point.

Loving someone is hard. This is what Meat Loaf teaches us. Sure, love is great, exuberant, sexy, bombastic, self-dissolving, but in addition to all of these things, loving someone is tedious, repetitive, and boring. We all love Meat Loaf, for the expansiveness of his performances, for the queerness of his emotions, for his unabashed horniness... An essay written around the time of Meat Loaf's death, about his intense and complicated depiction of love.

I Think You Should Leave is a TV show about desperate, sad characters inhabiting moments of embarrassment, horror, and absurdity, out of which the show’s comedy arises. An attempt to understand the place of cringe comedy today.

In The Topeka School, Ben Lerner narrates the world that created the one in which we now live. A long review of Ben Lerner's The Topeka School (pdf available at the link).

Whereas many of us post nearly all the time, Lockwood elevates it to an art. I wrote about the way that Patricia Lockwood's novel modulates the experience of living on and off the internet.

The song promises an ability to inhabit a space of ridiculous and contradictory desire—to the point of self-dissolution—without feeling ridiculous or contradictory. A personal essay about listening to Bonnie Tyler's "Total Eclipse of the Heart" as a child.

Since time immemorial, there have been Foucault gays and there have been Marx gays, and they do not get along... In this review, I thought through the contributions of a beautiful work of history and theory by the late Christopher Chitty.

But these aren’t just stories. Narratives about Silicon Valley, even skeptical ones, crucially rely on the infrastructure—both literal and imagined—provided by the tech industry, as that industry dictates what is possible, desirable, or, simply, “better.” On Anna Wiener's Uncanny Valley and HBO's Silicon Valley and the way that the stories we tell about tech are hardly new.

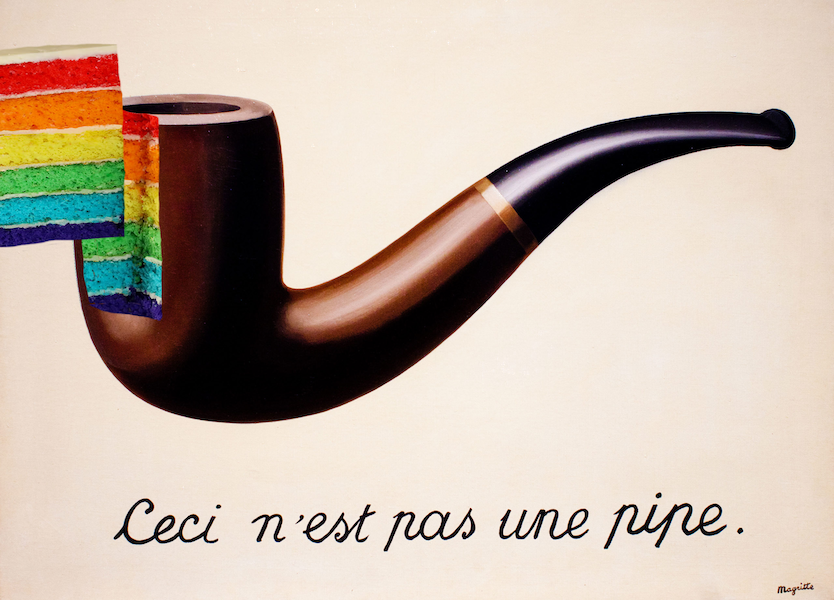

Reality’s representation seems life-or-death in the context of a virus that you can spread without even displaying symptoms, but mimesis’s coexistence with the ordinary world goes back at least to Zeuxis and Parrhasius. “The cakes,” as we’re calling them, play into these questions of perception and reality, and part of their potency comes from the ambivalent—simultaneously fascinated and horrified—responses they produce. We can’t look away from the very thing that makes us disbelieve our eyes, and yet that thing of disbelief is, bizarrely, familiar. On cakes that look like other things and the strange phenomenal experience of our present.

When you don’t have a job, you’re always working. An essay on the way HBO's anthology series High Maintenance represents labor.

Through their literary investigations, these authors challenge many of the assumptions about history, race, and gender that underlie their Gothic predecessors. They understand the way that history preserves certain stories while precluding others.

DeWitt uses fiction to elucidate the conditions that allow people to create brilliant and beautiful things. Sometimes her characters make literature, but they also make suits, compromises, money, music, businesses, deals, and love. A review of DeWitt's short story collection Some Trick.

Unfortunately, the website on which this review appeared no longer exists.

Mornings are normal, but they are not regular.

Unfortunately, the website on which this review appeared no longer exists.

This exploration begins subtly, almost anxiously, in Walsh’s opening story, “Two.” As the narrator describes her life as a roadside vendor, waiting to sell her sole companion — a vaguely described statue of two figures nestled together — “Two” (like many of Walsh’s stories) becomes more about the way it is told than its actual narrative content.

Giono blends Herman Melville’s life through the genres of personal essay, literary criticism, and biographical novel, relishing the possibility that our understanding of an author might largely be an effect of that author’s fictional creations. One of my first pieces of published writing, on Jean Giono's book on Melville.